When Food Tastes Fine But Still Feels Wrong

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR BLOG

Promotions, new products, and recipes.

Partially eaten meal with resting fork — suggesting attention faded before the experience did.

The Experience

It usually happens halfway through the meal.

The first bite is fine. Sometimes even good. The flavors register correctly. Salt is salt. Sweetness lands where it should. Texture behaves.

And yet, a few bites in, something flattens.

Not disgusted. Not disappointment in the obvious sense. Just a quiet sense that eating is no longer doing what it’s supposed to do. You keep chewing, but the experience stops unfolding. The food doesn’t invite attention. It doesn’t resist it either.

You notice yourself speeding up.

Not because you’re hungry, but because there’s nothing left to wait for. No surprise, no tension, no reason to linger. The meal becomes procedural. Calories are moving through, but the pleasure curve has already peaked and dropped.

Sometimes this happens with foods that look respectable. Nothing fluorescent or cartoonish. Labels read clean enough. Ingredients sound familiar. You might even think, objectively, that the food is “better” than what you grew up with.

And still, you push the plate away earlier than expected.

Or you finish it and feel oddly underfed, not in quantity but in experience. As if your body registered the input, but your attention didn’t get paid.

People often describe this feeling as boredom. Or blame their mood. Or assume their tastes have become jaded.

But the sensation is remarkably consistent.

Different cuisines. Different price points. Different settings.

The same muted ending.

The Wrong Explanation

The most common explanation is that food has become unhealthy.

Too processed. Too sugary. Too artificial. Too optimized for cheap pleasure.

There’s truth there, but it doesn’t reach the problem described above.

Because the feeling shows up even when those variables are stripped away. Even when the food is restrained. Even when sugar isn’t doing the heavy lifting. Even when the ingredient list looks like something a human might actually cook with.

Another explanation is nostalgia.

That food has not changed. That memory edits the past generously, sanding down the dull meals and preserving only the exceptional ones. That adulthood brings distraction, stress, and dulled senses.

This also explains part of it, but not enough.

If it were only nostalgia, the disappointment would be random. Some meals would break through. Some wouldn’t. Instead, the flatness is predictable. Systematic.

Then there’s the idea that expectations are too high. That social media and constant comparison have trained us to demand novelty and intensity from every bite.

But this assumes the problem is excess desire.

What people actually describe is the opposite.

They aren’t craving fireworks. They’re craving continuity. A sense that the meal is going somewhere. That each bite earns the next.

The wrong explanations all treat the problem as a failure of restraint, memory, or self-control.

They miss the possibility that something structural has changed in how food is designed to be experienced.

What is Actually Happening

If you want to understand the feeling, it helps to stop thinking about food as a collection of ingredients and start thinking about it as a sequence.

Eating isn’t a single event. It’s a progression.

A good meal doesn’t deliver everything at once. It reveals itself. Flavor develops. Texture shifts. Aromas rise and fall. Small resistances chew, heat, density slow you down just enough to keep attention engaged.

Modern food often collapses that sequence.

Not by accident, but by design.

Many foods are engineered to deliver their primary sensory information immediately. The salt is upfront. The sweetness is clear. The fat coats quickly. Within seconds, your nervous system has received most of what the food has to say.

After that, there’s nothing left to discover.

This isn’t about intensity. It’s about pacing.

When everything arrives at once, the experience ends early, even if you’re still eating. Your mouth is busy, but your perception has already moved on.

Another shift happens at the level of texture.

Foods that are too consistent, too smooth, too uniform, too predictable. Don’t ask much of the eater. You don’t need to change how big your bites are, how long you chew, or pay much attention.

Your body can eat on autopilot.

Autopilot feels efficient.

It also feels empty.

In older food systems, inconsistency was normal. Variations in firmness, moisture, bitterness, or density created micro decisions while eating. These weren’t conscious choices, but they kept the eater involved.

Modern food minimizes those variations. Stability is rewarded. Surprise is treated as a defect.

Finally, there’s the issue of resolution.

Many foods now lack a clear ending. Flavors don’t taper. They plateau and stop. There’s no sense of completion, only cessation.

The body notices this.

Not as a thought, but as restlessness. The meal ends, but the system that evaluates satisfaction doesn’t receive a clear signal.

So, you feel fed but not finished.

Why This Keeps Happening

None of this requires bad intentions.

It emerges naturally from the pressures shaping modern food.

Shelf-life rewards sameness. Predictable textures travel better. Stable flavors last through time and heat.

If food tastes the same on day 1 and day 60, it’s easier to ship, easier to make more of, and easier to trust.

Clean labeling adds another constraint.

When the number of acceptable tools shrinks, the remaining ones are pushed harder. Fewer levers are asked to do more work. Sensory delivery becomes more compressed, not because anyone wants dull food, but because there are fewer acceptable ways to build depth gradually.

Cost pressure narrows the margin for inefficiency.

Long, unfolding experiences require time, variation, and loss. They assume some bites will be less perfect than others. Modern systems optimize away that unevenness.

Reformulation plays its part as well.

As products are adjusted to meet new expectations, fewer certain components, different sourcing, tighter margins the easiest thing to preserve is the initial impression. First bite matters most. Later bites are harder to justify on a spreadsheet.

Over time, this trains an entire ecosystem to focus on immediate clarity rather than sustained engagement.

What disappears isn’t flavor, exactly.

It is a conversation.

The quiet back and forth between eater and food, where attention is rewarded over time.

That absence doesn’t announce itself loudly. It just leaves meals feeling shorter than they are.

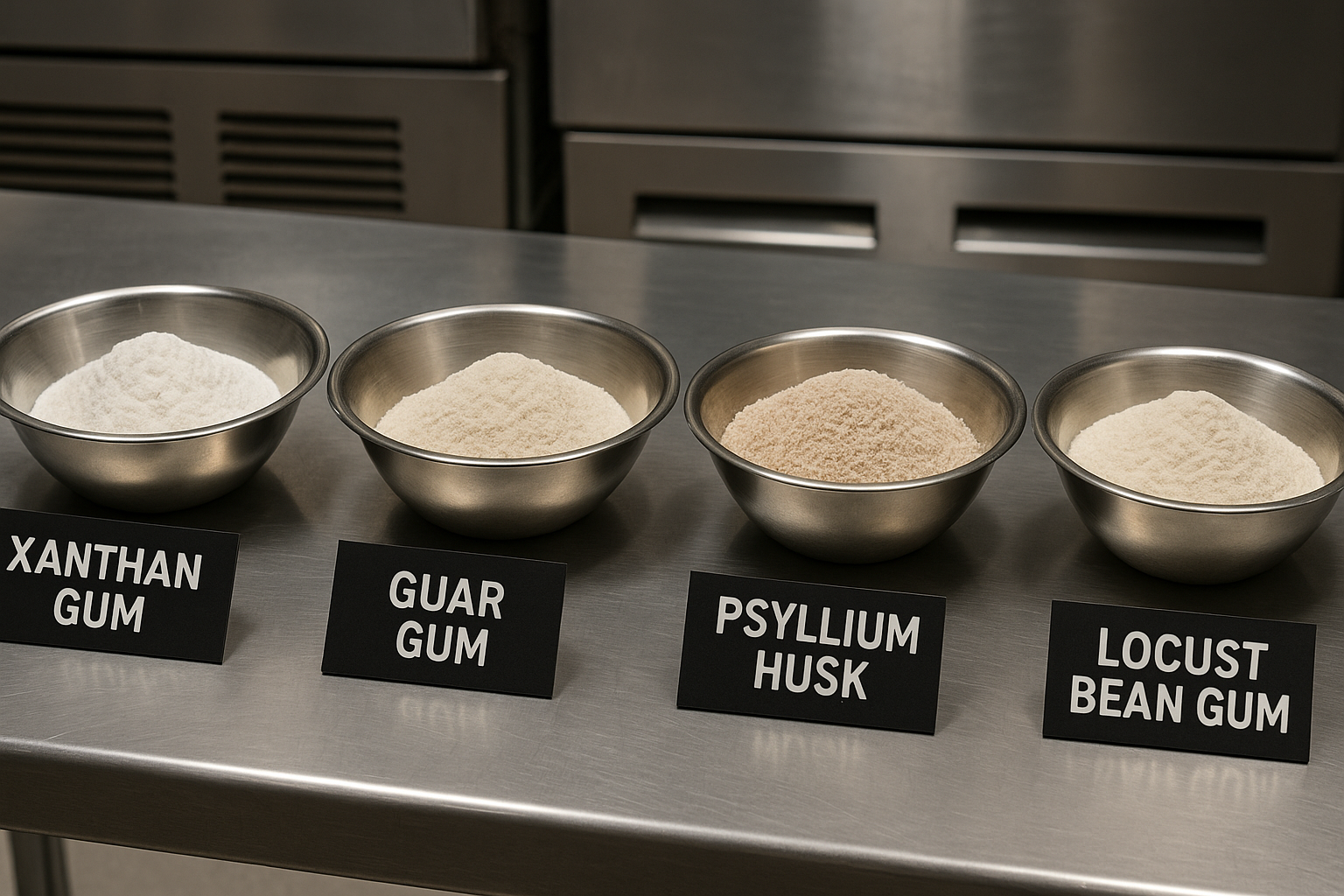

Knowing this, you can begin to glimpse how small structural choices silently decide whether food feels complete or hollow. Binding, hydration, sequencing.

These aren’t headline qualities. They do not announce themselves on a label or register as flavor notes. But they determine how information is shared over time. How long resistance lasts.

Whether texture changes or remains stable. Whether the last bite feels like a conclusion or just the moment you stop eating. When those choices are compressed or flattened, the eater doesn’t consciously notice what’s missing.

They simply lose interest sooner than expected. Satisfaction fades before fullness arrives. The meal technically succeeds, but experientially never quite lands.

|

About the Author Ed is the founder of Cape Crystal Brands, editor of the Beginner’s Guide to Hydrocolloids, and a passionate advocate for making food science accessible to all. Discover premium ingredients, expert resources, and free formulation tools at capecrystalbrands.com/tools. — Ed |

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe to The Crystal Scoop

Food-science tips, ingredient know-how, and recipes. No spam—unsubscribe anytime.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.