Gellan Gum Gel: Creating Clear and Heat-Stable Gels: Techniques and Recipes

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR BLOG

Promotions, new products, and recipes.

Gellan Gum Gel Introduction

Gellan gum gels are often though of like it’s some kind of magic trick. “It makes gels clear.” “It’s heat-stable.” “It can replace gelatin.” All of that is partly true, but it’s usually said in a way that makes it sound effortless. Like you just sprinkle it into a liquid, heat it once, and you’re suddenly holding a flawless, crystal-clear, heat-stable gel in your hands.

In real kitchens and real product work, it’s never that neat.

The reason gellan gum gets worshipped is the same reason it frustrates people: it’s unusually sensitive to context. The difference between a clean, elegant gel and a cloudy, brittle slab that leaks water overnight can be a tiny shift in calcium, sugar, acid, or how aggressively you shear it during hydration. This comes up constantly when someone “follows the recipe” but changes the juice brand, or uses a different mineral water, or decides to add lemon “just a splash.”

And suddenly the gel is wrong.

When gellan does what it’s supposed to do, the effect is honestly beautiful: clear gel formation, sharp cuts, tight edges, no wobble, no haze. But that beauty comes from a very specific kind of network, and the network is picky. If you understand the network, you stop blaming the powder and start diagnosing the system.

That’s really the whole game.

Gellan gum

Gellan gum is one of those ingredients that feels like it belongs more in a lab than a bakery, but bakers are the ones who end up falling in love with it. Mostly because it behaves like a grown-up. It doesn’t melt into soup the moment you warm it. It sets cleanly. It slices like you meant it.

The real selling point isn’t “it gels.” Lots of things gel. The real selling point is how it builds structure. And how you can steer that structure toward clarity, firmness, elasticity, brittleness, or heat resistance depending on what you’re trying to accomplish.

People sometimes forget gellan is a microbial polysaccharide. It’s made by fermentation, and then purified. That matters because it doesn’t come with the same flavor baggage as some plant extracts, and it tends to feel “invisible” in the mouth when used correctly. That invisibility is a feature. It’s also a risk, because it’s easy to overdo and create a texture that feels like a plastic insert.

And yes, there are types of gellan, which is where most confusion starts.

High-acyl gellan is softer, more elastic, more like a delicate elastic gel. Low-acyl is firm, brittle, very clean-cut, and the one most people mean when they say “clear and heat-stable.” A lot of pastry work leans low-acyl. Most “heat-stable dessert gels” you see are basically low-acyl gellan doing what it does best: forming a rigid network that doesn’t collapse when warmed.

Now… it’s not bulletproof. It’s stable until it isn’t. You can absolutely break it with the wrong acid level, ion content, or processing, and I see this often when people try to force gellan into fruit systems without thinking about calcium and pH.

That’s where the real craft begins.

Heat resistant gels

“Heat resistant gels” is one of those phrases that makes everyone relax too early. Like the problem is solved. But heat resistance isn’t a single property. It’s a set of tradeoffs.

A gel can resist heat because:

-

it doesn’t melt easily,

-

it doesn’t weep under warm holding,

-

it doesn’t soften into a puddle at service temperature,

-

it stays sliceable even under lighting heat,

-

or it retains shape during baking.

Those are different demands. And gellan can satisfy some of them brilliantly… while failing others if you treat it casually.

Here’s the part people miss: gellan gels “lock” via an ordered network, and that network tightens with the presence of ions (especially calcium). That tightening is what pushes you toward a firmer, more heat-stable gel. But tightening also pushes you toward brittleness and syneresis if you go too far.

So you’re always balancing. You’re always negotiating.

This is where gellan gum gel properties actually get interesting. The gel is not just “set or not set.” It has geometry. It has a skeleton. In the language of food science, you’re controlling gel structure in food, meaning the arrangement and density of the network, how water is trapped, how fractures propagate, and how light passes through.

That last part—light—is why people chase clarity. Clarity is a proxy for order. If the network forms evenly and the phases match well, you get a glassy look. If you get microphase separation, tiny insoluble particles, or uneven hydration, you get haze. Sometimes it’s not even the gellan. Sometimes it’s fruit pulp, protein, minerals, or air bubbles you whipped in while blending.

One small but real trick: clarity loves calm. Over-shearing and foaming is the silent killer of clear gel formation. People want to blast with an immersion blender because it “mixes better.” Sure. It also aerates. And microbubbles love to hang around like ghosts, ruining a gel you technically executed correctly.

Heat resistance also depends on concentration. That sounds obvious, but it’s not linear. There’s a point where adding more gellan gives you more rigidity but a worse eating experience. And eating experience matters. If you’re making a heat-stable dessert gel that feels like snapping through acrylic, congratulations, you solved the wrong problem.

Heat-resistant raspberry gel

Raspberry is a great example because it’s delicious and it behaves like a troublemaker.

It’s acidic. It contains suspended solids. It has pectin fragments. It brings its own chemistry to the party. If you just treat it like flavored water, you get punished.

A clean heat-resistant raspberry gel tends to work best when you decide upfront what you care about most: a perfectly clear ruby jewel, or an intense fruit puree gel with body and opacity. Trying to get “perfectly clear” while using a gritty puree is how people end up frustrated.

A straightforward professional approach is something like this:

You decide the liquid base. If you want it clear, use a clarified raspberry juice or a strained infusion. If you’re okay with a natural-looking gel, puree works, but accept the haze.

Then you decide what kind of gel you want:

-

firm sliceable insert,

-

soft elastic gel,

-

hot-holding garnish gel,

-

pipable gel that sets after plating.

Those are different.

For a classic heat-resistant insert style, low-acyl gellan is the backbone. Typical ranges are small—this surprises people. It’s not like agar where you’re used to bigger percentages. You’re often playing in fractions of a percent, and that’s enough to swing texture from elegant to aggressive.

You hydrate properly. That means you actually bring it up to a real boil (or close), long enough to fully solubilize. You can’t half-heat it and expect the network to form cleanly. This is another place people get confused, because gellan doesn’t “act” hydrated until it suddenly does.

Sugar complicates things. Sugar competes for water, thickens the continuous phase, and shifts the perceived firmness. Sometimes sugar makes the gel feel more luxurious. Sometimes it makes it set weird. And if you’re dealing with a high-solids fruit base, the system can behave like a completely different ingredient.

Acid is the trap. Acid isn’t automatically bad, but low pH can weaken the network depending on the exact setup and ion environment. That’s why you’ll see recipes that set fine at first and then soften after a day in the fridge. The network reorganizes, water migrates, and you get a gel that feels “tired.”

If you want it truly heat-stable, you usually want a controlled calcium environment. Some systems accidentally contain enough calcium (from fruit, dairy, or water). Others don’t. And we don’t actually have perfect data on this in a kitchen sense because water and fruit mineral content varies wildly. You can measure it, sure, but most pastry chefs aren’t running ion chromatography mid-service.

So you learn by pattern recognition.

This comes up often: someone gets an amazing gel one day and can’t reproduce it the next week. Same “recipe,” different water source, different raspberry lot, different acid content. Gellan isn’t inconsistent. The system is inconsistent.

Related pastry chef articles

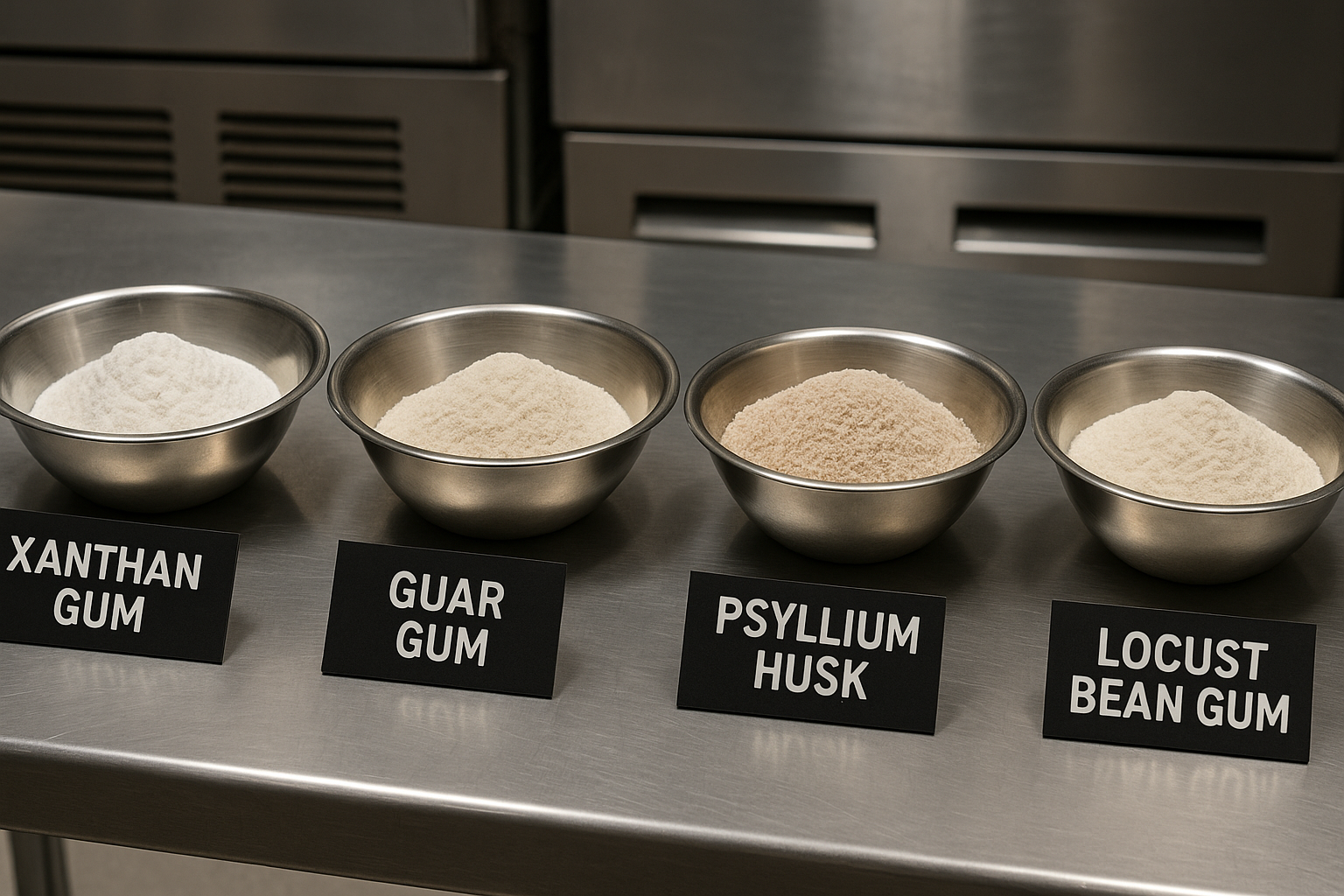

The pastry world tends to treat gellan like a “modernist tool,” but it’s more basic than that now. It’s just another structural ingredient, like gelatin, agar, pectin, starch, carrageenan. It’s not exotic anymore. It’s just… under-understood.

What I like about the pastry community is they care about outcomes. They’re less impressed by the chemistry story and more impressed by whether the gel cuts cleanly, holds on the plate, survives the pass, and doesn’t bleed into a mousse.

That practical obsession is where gellan shines. It lets you build gels that behave properly in modern plated desserts. And once you see it, you stop wanting to go back. Not because gelatin is “bad,” but because gelatin is emotionally needy. It wants refrigeration. It wants gentle handling. It wants you to stop warming the plate. It wants the dining room temperature to behave.

Gellan doesn’t care nearly as much.

But I’m also not going to pretend it replaces everything. That myth shows up a lot: “Gellan is just gelatin but better.” No. Gelatin has melt-in-mouth behavior that gellan rarely replicates cleanly. Gelatin has a specific kind of elasticity and bloom-driven pleasure. Gellan can mimic some of that with blends, but it becomes a different strategy. You’re building a composite structure, not a swap.

If you want a gel that disappears as it warms on the tongue, gelatin still owns that lane. If you want a gel that holds shape under mild heat and cuts sharply, gellan is your friend.

And sometimes you want both. People do this more than they admit.

Sources

This is the part where a lot of internet content gets goofy. People cite a sentence from a datasheet, then repeat it like scripture: “Forms a gel at low concentration. Heat stable. Clear.”

Yes. But those are labels, not understanding.

Most of the meaningful “sources” for gellan behavior are:

-

supplier technical sheets,

-

pastry testing notes,

-

internal product development experience,

-

and the occasional academic paper that’s too clean to reflect kitchen chaos.

That’s not a complaint. It’s just the reality. The academic literature often uses purified systems. Kitchens don’t. Food systems aren’t clean. They’re messy, full of minerals and competing hydrocolloids and proteins and acids. That mess is exactly where gellan gets interesting.

Uses

In practice, gellan gets used for a few recurring jobs.

Clear gel formation for:

-

fruit gels,

-

cocktail cubes,

-

beverage pearls,

-

layered inserts,

-

suspended particulates (when tuned right).

Heat-stable gels for:

-

warm-held plated components,

-

bakery applications where you don’t want the gel to slump,

-

fillings that survive baking or reheating,

-

decorative elements that stay sharp under lights.

And then there are the weird uses: stabilizing suspensions, creating fluid gels, pseudo-custards, hot gels that set on the plate. Those are the ones chefs talk about late at night, when they’re half-proud and half-annoyed at what they’ve gotten themselves into.

Foods

If you’re wondering where you’ve already eaten gellan, the answer is: probably lots of places. It shows up in plant-based milks, flavored beverages, dairy alternatives, sauces, certain confectionery systems, sometimes even in things like icing or bakery fillings where stability matters.

Most people never notice it, which is kind of the point.

It’s one of those ingredients that’s more about preventing failure than creating a signature flavor. It’s there because the product needs to ship, sit, hold, reheat, and still behave.

Benefits vs Risks

The “is it bad for you” question always lands in the same place: it depends heavily on context.

Gellan is used at very low levels in foods. It’s not a nutritive ingredient. It’s not there to nourish you. It’s there to create structure. If you’re the type of person who believes any additive is automatically suspicious, then sure, you’ll classify it as “bad” because it’s unfamiliar.

But that’s not a scientific stance. That’s a cultural stance.

From a functional standpoint, gellan is generally used in tiny amounts, and most people tolerate it fine. Some individuals report GI sensitivity to gums broadly, but that’s not unique to gellan. And it’s hard to cleanly separate “this gum caused it” from “this ultra-processed product caused it” or “this person is sensitive to fermentable fibers and polysaccharides generally.”

That’s true in theory, but in real eating patterns, the dose matters. If you’re having a few grams of gellan across a day, something has gone very wrong in product design. Most of the time you’re consuming milligrams.

There’s also the philosophical side: are we using these ingredients to make better foods, or to make worse foods seem acceptable? That’s where people argue. And I get it. Hydrocolloids can be used to make genuinely elegant things… or to prop up garbage.

Gellan doesn’t decide. Humans do.

Datasheet

If you read a gellan datasheet, you’ll see the same repeat claims: clear gels, heat stability, ion sensitivity, low usage rates. The part that usually matters most is buried: hydration temperature, recommended shear, and how ions influence set strength.

And even then, it’s not a full story. Datasheets can’t predict your raspberry puree, your tap water, your pH drift, your sugar solids, your blending habits.

Ideas for use

I’ll say this plainly: if you’re trying to “learn gellan,” stop making complicated recipes first. Use it in a controlled clear system. A simple flavored water gel. A clarified juice gel. Something where you can see what it does without fruit pulp and acid chaos.

Then move into more complex systems like puree gels, dairy gels, blended gels. Your brain starts building a library of behaviors. You stop guessing. You start predicting.

The people who hate gellan are usually the ones who tried it once in a messy system and decided it was unreliable.

It’s not unreliable. It’s just not forgiving.

Technical remarks

A few things that sound boring but determine success:

Hydration matters. Heat matters. Time at temperature matters. So does cooling rate.

Ion content matters far more than people expect. “My water is just water” is one of the biggest lies in food work. Minerals are chemistry. Gellan listens to minerals.

Acid matters, but not always immediately. Sometimes the gel looks perfect, then relaxes over time. That delayed failure is the part that makes people distrust it.

Blending matters. Foam ruins clarity. Microbubbles persist. The gel traps them like amber.

And finally: concentration isn’t just “more = stronger.” More can mean brittle, weepy, unpleasant. Structure is not the same as pleasure. You can engineer a flawless gel that nobody wants to eat.

FAQs

What is gellan gum?

Gellan gum is a fermentation-derived hydrocolloid used to create gels and stabilize textures in foods. It’s valued for its ability to form very clear gels at low concentrations and for building structures that can hold up under heat when properly formulated.

Where does gellan gum come from?

It comes from microbial fermentation. A specific bacterium produces the polysaccharide, which is then purified and dried into powder form for food use.

What is gellan gum used for?

It’s used for clear gel formation, suspension in beverages, structured dessert components, bakery fillings, plant-based dairy textures, and heat-stable gels that need to hold shape beyond refrigeration conditions.

What foods contain gellan gum?

You’ll see it in some plant milks, flavored drinks, dessert gels, sauces, fillings, and certain processed foods that need stable texture or suspended particles.

Is gellan gum bad for you?

Most people tolerate it fine at typical use levels, which are very low. Some individuals may be sensitive to gums broadly, but blaming gellan specifically is usually an oversimplification. The bigger question is typically the overall food matrix and how often someone consumes heavily structured, additive-dependent products.

Conclusion

The thing I keep coming back to with gellan is that it’s not “hard,” it’s just honest. It reflects what you built. If the system is unstable, the gel shows you. If the system is balanced, the gel rewards you.

And once you’ve gotten a few truly clean, heat-resistant gels under your belt, ones that stay sharp on the plate, ones that don’t melt into panic under warm service, you start to see why people keep circling back to it, even after they swear, they’re done with it…

|

About the Author Ed is the founder of Cape Crystal Brands, editor of the Beginner’s Guide to Hydrocolloids, and a passionate advocate for making food science accessible to all. Discover premium ingredients, expert resources, and free formulation tools at capecrystalbrands.com/tools. — Ed |

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe to The Crystal Scoop

Food-science tips, ingredient know-how, and recipes. No spam—unsubscribe anytime.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.